Hallstatt

Dec 10, 2016 – Feb 17, 2017

Curated by Maria do Carmo M. P. de Pontes and Kiki Mazzucchelli

Opening

Dec 9, 8 pm–10 pm

Galpão

Rua James Holland 71

São Paulo

Directions

Download

Alexandre da Cunha | Tamara Henderson | Tobias Hoffknecht | Iman Issa | Oliver Laric | Candice Lin | Manoela Medeiros | Nuno Ramos | Mauro Restiffe | Joshua Sex | Amie Siegel | Daniel Sinsel | Caragh Thuring

Hallstatt takes the notion of duality as the starting point for a reflection on the meaning of repetition of signs, images and forms in the contemporary context. The idea of duality has structured Western thought at least since the creation myth, having become a recurrent theme in literature and psychoanalysis from the nineteenth century onwards. The exhibition brings together works by thirteen artists whose practice deal with duality by means of distinct strategies. In Hallstatt, duality is understood both in its most fundamental meaning – through formal symmetries – or philosophically and existentially as a state of altered perception, copy, recycling or an index of parallel realities. By raising more questions than providing definite answers, the exhibition intends to broaden the discussion about the theme, which becomes so urgent at a time when absolute truths are increasingly disseminated – and the place of truth has become harder to identify.

Alexandre da Cunha (Rio de Janeiro, 1969. Lives in London), is best known for his sculptures that revisit and reframe objects of daily use. His canvases – seen by the artist as wall sculptures rather than paintings – follow the same logic, incorporating materials such as mops, hats, seashells and brushes. The series Amazons (2014 – in progress) features beach towels with bold prints as raw material. Each piece from Amazons brings together a group of identical towels, which Da Cunha himself dyes – giving each part different degrees of sharpness – and then sews together, emphasising notions of accumulation and repetition.

Tamara Henderson (New Brunswick, Canada, 1982. Lives in Canada) produces mostly sculptures and installations – functional, at times – that she conceives while in an altered state of perception, whether under hypnosis, on barbiturates or during sleep. In Hallstatt, Henderson shows two large curtains produced while in residence at Hospitalfield House in Arbroath, Scotland. The works function as a portal to a parallel reality imagined by the artist, a transition element that signals the movement of passage from one dimension to another. Each of the pieces synthesises the subjective imagery associated with these realities, consisting of, in the words of the artist, ‘postcards of a porthole’.

Tobias Hoffknecht (Bochum, Germany, 1987. Lives in Cologne) graduated from the Academy of Arts (Kunstakademie) in Dusseldorf in 2013, where he studied under the guidance of Rosemarie Trockel. By adopting a minimalist aesthetic, Hoffknecht produces installations usually composed of pairs of sculptural elements that create different relations between the viewer and the exhibition space. Extremely well-finished, his pieces resemble industrial ready-mades, although they are unique works manufactured according to the artist’s specifications. Thus, they establish a close dialogue with design, often evoking furniture or directly interfering with the architecture of the exhibition space. In Hallstatt, Hoffknecht presents two newly commissioned sculptures in wood and stainless steel, materials he employs time and again in his practice.

In the series of sculptures titled Lexicon (2012 – ongoing), Iman Issa (Cairo, 1979. Lives between Cairo and New York) revisits existing artworks, which are presented as studies for contemporary remakes. While retaining the tiles of the original drawings, paintings, sculptures, or photographs, the resulting works are not faithful reproductions or copies, but interpretations whose forms differ significantly from their sources. By offering alternative forms to these works, she attempts to communicate something more familiar and consistent with her experience of what she thinks these titles are referring to. The sculptures are accompanied by museum captions that contain brief descriptions of the originals, as well as their provenance and date, offering clues about the identity of their source without completely revealing them.

Since the beginning of his artistic practice about ten years ago, Oliver Laric (Innsbruck, Austria, 1981. Lives in Berlin) takes copy, appropriation and re-signification as guiding axes to his work. In Hallstatt, Laric shows two sculptures that were part of his recent exhibition at Secession, Vienna (Photoplastik, April – June 2016), in which he produces 3D scans of public sculptures found in the same city – in this case, the Monument to Auguste Fickert by Franz Seifert (1929) and Polar Bear and Seal, by Otto Jarl (1902) – and reprints them in polyamide. The artist makes all these scans available on a website, where anyone can download them, also alluding to the notion of dispersion.

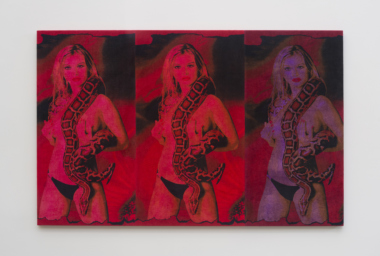

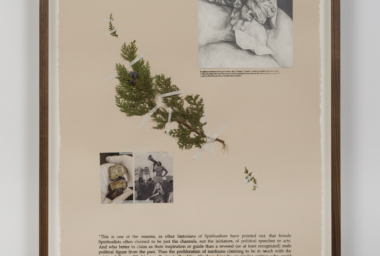

Candice Lin (Concord, Massachusetts, 1979. Lives in Los Angeles) makes use of various media to carry out a detailed investigation on the animal kingdom, with a specific focus on natural phenomena and microorganisms such as fungi and bacteria. Hormonal Fog (Study #1) [2016, in collaboration with Patrick Staff] consists of a smoke machine that intermittently emits a substance that blocks the production of testosterone. In the collages shown at Hallstatt, the artist explores narratives on natural phenomena that have been historically marginalized by science: records of men who produce breast milk, stories about female mediums who channel renowned male politicians, amongst others. Framed in the characteristic manner of samples in ethnographic or natural history museums, these works trace a kind of parallel history of science that disrupts traditional binary categories associated to gender, cultural practices and reproduction.

The sculptures, paintings, performances and installations by Manoela Medeiros (Rio de Janeiro, 1991. Lives in Rio de Janeiro) focus on the body and its relations with time and space. The allusion to skin and permeability is a recurring element both in the works where she uses her own body and in the site-specific installations where she works on wall surfaces to create environmental compositions. In the latter process – a version of which she developed specifically for Hallstatt – Medeiros obsessively scrapes sections of the wall surface and creates reflections of the forms produced by her action, sometimes using the paint peeling residues or incorporating other three-dimensional elements into the work.

Nuno Ramos (São Paulo, 1960, where he lives and works) explores notions of duality, mimesis, intertextuality and repetition using different languages and media, including text, image, sound and plays. In Hallstatt, Ramos shows the ephemeral installation 3 cinzas (Ai, pareciam eternas!) [3 Ashes (Oh, they seemed eternal!)], made with lime, ash and salt. Using these three materials, the artist has reproduced the outline of the facades of three houses in which he lived – his grandmother’s, his mother’s and the house where his children were born – on the gallery floor. During the exhibition, the lines will be gradually spread by the action of visitors’ footsteps and the wind. The work alludes to Ramos’ 2012 site-specific installation 3 lamas (Ai, pareciam eternas!) [3 Muds (Oh, they seemed eternal!)], but above all to the displacement of affective sites and memory. Ramos is also showing the piece Un Coup de Dés, a version in glass and acid of Stéphane Mallarmé’s Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’Abolira le Hasard (1897), which is considered as the first typographic poem in history. In Ramos’ version, overlapping glass sheets allow the glass-etched verses to be read in their entirety. The artist also contributes to the exhibition with the essay Bonecas russas, lição de teatro (Russian Dolls, Theatre Lesson), originally published in his book Ó (2008), and reprinted in the exhibition catalogue.

Mauro Restiffe’s (São José do Rio Pardo, 1970. Lives and works in São Paulo) photographs are invariably produced by means of analogical procedures and always in B&W, which allows him to obtain a much wider range of shades and textures than digital photography. Over the last three decades, Restiffe has developed a solid body of work in which art and architecture are recurring subjects. The architecture of Brasília and its cultural and political symbolism is the background to two series produced respectively at the occasion of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Siva’s inauguration (Empossamento [Inauguration], 2003] and Oscar Niemeyer’s funeral (Oscar, 2012), from which one image is shown in Hallstatt. By registering the same location after an interval of time, the artist establishes a relation of duality between the series that actualises and re-signifies the images. The exhibition also includes another two works from the series Russia (2015), which underline Restiffe’s interest in capturing images (paintings, photographs, etc) within the photographic image, like a kind of matrioshka that highlights the dialogical relationship between spectator and image, as well as the illusory nature of images.

Joshua Sex (Dublin, 1985. Lives in London) is a painter and writer whose work is inextricably linked to the notion of recycling. During his Master’s degree at the Royal College of Arts in London (2011 – 2013), the artist began to appropriate fragments of discarded canvases in the hallways of the university, using them as a basis for his compositions. What began out of necessity or amusement became his modus operandi, and from then on the artist always needed these clues in the form of vestiges to compose his canvases. In Hallstatt, Sex presents a set of five paintings produced between 2012 and 2015.

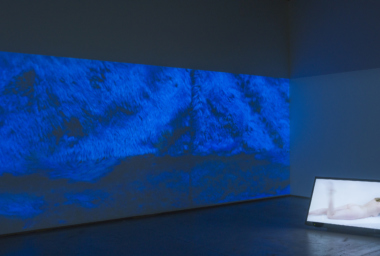

Amie Siegel (Chicago, 1974. Lives in New York) works mainly with audio-visual installations that deal, in myriad ways, with notions of duality. The video Genealogies (2016) is somewhat an archaeology of the artist’s references, in which she articulates the idea that citations to other works are always present in supposedly original projects, taking Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt (1963) as a case study. This Godard classic is also explored in The Noon Complex (2016), a double projection accompanied by a television screen in which she deconstructs Contempt by digitally removing Brigitte Bardot from the narrative. The screen shows an actress re-enacting Bardot’s movements, prompting the viewer to dialectically overlap images so as to produce a full narrative.

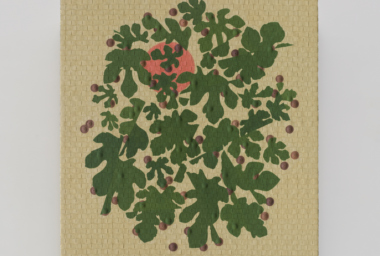

Daniel Sinsel (Munich, 1976. Lives in London) incorporates organic materials such as seeds or animal skins into compositions that cut through the two-dimensional surface of the canvas, which lends them a sculptural quality. His first works, produced in the early 2000s – many of which portrayed young naked or semi-naked men – already explicitly indicated his interest in exploring the notion of eroticism in painting. This theme recurs throughout his practice, even in works where this reference is less evident. In the two recent paintings presented in Hallstatt, for example, eroticism is evoked by the relation created between what is on and off the canvas and what is offered or concealed from viewers. Moreover, by incorporating objects whose materiality is not completely distinguishable, the works create a kind of tromp l’oeil that raises doubts about which elements are real and which are represented. Painting/ sculpture, inside/ outside, reality/ representation are just some of the dualisms that permeate Sinsel’s production, a practice that hinges above all on a seduction game established between viewer and work.

The paintings by Caragh Thuring (Brussels, 1972. Lives in London) pervade notions of duality by means of different gestures. For instance, the hybrid image of a volcano and a pyramid – and, more fundamentally, the brick that makes up this hybrid – is a recurring image in her work. Other paintings are inspired by compositions of canonical artists, such as Édouard Manet and Filippo Brunelleschi. Yet other of Thuring’s works are simply pairs, as she sees them, one part being dependent on the other to exist. Here, the artist shows three almost identical pieces that depict volcanoes – embroidered versions of a drawing she made in early 2016, which in turn was inspired by nineteenth-century Neapolitan gouaches –, phagocytising her own work by mixing notions of figure and background. Thuring also shows two other works in which she paints bricks to compose human figures on contrasting scales: three miniscule men posing in David Gandy (2014) and a gigantic woman in Brick Lady (2013).

Also in exhibition are five pairs of dishes, belonging to two São Paulo-based private collections and dated between 1750 to 1860. Whereas some of them have been acquired as pairs, in other instances the collectors bought one piece and waited for years until they found its double. As they are hand-painted, each of the parts present small differences in relation to its pair – a bigger flower, a tree with thicker foliage and so on – inviting the viewer to carefully examine them, as in a ‘spot the differences’ puzzle. There is one curious exception, where the discrepancy is at first evident; after a closer examination, one realises that while both centres present different palatial scenes, their borders repeat the same pattern.

Hallstatt is a picturesque village situated on the edge of a lake surrounded by mountains in Austria. About five years ago, it received a huge influx of Chinese tourists – more than usual, even for a place whose core economy is tourism. One of them, unsuspectingly, told a local resident that an identical copy of Hallstatt was in an advanced state of construction in the Guangdong Province of China, to the surprise of the almost 1,000 villagers who had not been consulted. Indeed, China makes a habit of reproducing Western monuments on its soil, but for the first time it had copied an entire city. This appropriation is especially symbolic considering that Hallstatt has the oldest salt mine in the world and is one of the oldest archaeological sites in Europe. In a way, this is the ultimate copy: the appropriation of the matrix of a culture.