Judy Chicago & Leda Catunda

Mar 12 – Apr 23, 2022

Opening

Mar 12, 2 pm–6 pm

FDAG Barra Funda

Download

Propelling Members, Founding the World: To Pronounce It

By Julia de Souza

Grammar is politics by other means

Donna Haraway

In the introduction to The Autobiography of Red, poet Anne Carson puts forward that ‘Nouns name the world. Verbs activate the names. Adjectives come from somewhere else’ and are in charge of ‘attaching everything in the world to its place in particularity’.

In her compositions, Judy Chicago picks the verb out of these three grammatical categories, formulating maxims and propositions that stimulate the contact with images and turn observations into a necessarily engaged gesture. This is the case for Do a Good Turn — an ambivalent title with its double meaning of ‘good deed’ and ‘good spin’. Each one of the fabric patches that make up the painting — in variations of orange and purple and placed symmetrically around the center that shows the printed title – illustrates the emblematic set of events preserving our species: copulation, confrontation, a child’s first steps, the walking sticks of old age. It is up to us to identify or not the diagram’s cyclical order, to weigh up its irony — and reflect on the figures’ indistinguishable gender.

In contrast, the works of Leda Catunda explore the intensive nature of adjectives that emphasize every single thing in the world. The adjectives used in her Portuguese titles appear almost invariably in their female form[1] — vermelha [red], recheada [stuffed], camuflada [camouflaged] — triggering a schism: do the content and quality of these compositions summarize or disturb the ideas and experiences of the female?

When considering the tension between the particular and the collective in some of Catunda’s work, such as Vermelha [Red] and Deusa [Goddess], we find the civility of undiscipline. Vermelha presents an aerial view, an archipelago, a fluvial map dyed red, in which a few islands coexist, harboring manga characters, circles that resemble buttons or ancient wax seals, Chinese characters overlaid on a Copacabana sidewalk, and the logo ‘Planet Girls’. The several protrusions in the large red landscape compete with the aerial cartographical aspect that we initially attribute to the work. The protuberances made of upholstered fabric, the scaly points evoking skin, the tassels that exceed any sign of smoothness, the fat drops that fall onto the floor – all of this makes us face the canvas up front, feet on the ground.

As such, something is being pronounced here. Originating from the Latin, ‘to pronounce’ means both to say, to make a sound, to speak, and to make something noticeable, to give salience, to bring forward, to project. To be pronounced is to jump up off the surface, and also to want to be enounced or propelled.

Between 1982 and 1985, Judy Chicago worked on the anthological series ‘Birth Project’, which resulted in more than 80 pieces designed by the artist and put together by more than 130 needleworkers from several different countries. During birth, which is the central motif in these works, something is also being propelled out: the newborn finally emerges into the world. In Birth Power, the vigor of the event is manifest in the warm colors that outline the female body, from whose womb a fire cascade erupts, in a link between the culmination of the creation of life and the power of a volcano. This incendiary ejection is also the element that interrupts the rigor with which Judy often draws the outline of her figures. In Smocked Figure, the lines making up the silhouette of a pregnant woman are precise, and the apparent indistinction between inside and outside, both in pale sand color, is nothing but a misconception: the mesh that composes the inside of the body is sewn horizontally, whilst the outside is made of vertical ridges. In both works, the woman is conjured through the re-enactment of emblematic events — to become pregnant, to give birth — therefore, through the reiteration of the verb.

Drawing on her research on the female and communal tradition of quilting, Chicago creates works whose structures evoke flags, banners or even shields, such as Hitch Your Wagon to a Star, in which a group of human figures appears inside a star positioned in the center of the painting, as if they were all embarking on the same multicolored journey towards faraway heights. What Chicago’s works are pronouncing here seems to be coming out of several mouths that sing in unison something close to Sappho’s verses: ‘we live [ ] the opposite [ ] Daring’.”[2]

In turn, Catunda is driven by an impulse to dismember. The two circles in Sisters, made of scraps of fabric, resemble two organs detached from corporeal totality. The two members, one larger than the other — could they be a symbol of reproduction? — are connected by two tubes as if they still preserved an organic trace within this small venous system.

If in Chicago the tongue of fire is the continuation of the woman’s body giving birth, Catunda’s tongues are separate or displaced. In Duas línguas [Two Tongues], an orangish tongue lasciviously sprouts from a red tongue, both using their viscosity to dodge the limits of a black frame. Exploring the destabilizing and exciting vocation of words, Catunda presents us with yet another tongue — this time titled Recheada [Stuffed]. In this flag made of several layers of overlaid fabric, in tones that move up from red to yellow and then down from yellow to red, a large hanging tongue threatens to suck in the entire world — and ourselves — with its monster lick. However, a hole traverses each one of its layers, putting at risk whatever lies stuffed in there. We could say that the hole represents the opening of the female sexual organ; however, more than that, the hole is a mouth. Leda Catunda’s ‘stuffed’ tongue is such a glutton that it also contains, in a subversion of the order of things, an oral cavity. It is, therefore, a mouth that is as stuffed as it is intensive, as open as it is devouring.

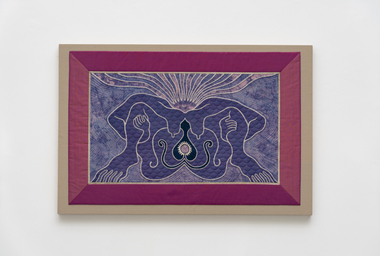

The reproductive female organ — traditionally associated with a vacuum, with a lack — also appears filled and agape in Chicago’s Childbirth in America. From its center, both in solar and floral ways, the event of genesis emerges.

In the essay The Gender of Sound, Anne Carson timely reminds us that women ‘have two mouths’; every mouth is a concavity aimed at deglutination, pronunciation and pleasure, and this triple threat triggers in men a response against such extravagance. ‘Silence is the kosmos [good order] of women’, Aristotle wrote in his Politics. Looking at the works of Judy Chicago and Leda Catunda, we see that both silence and good order are revoked: Chicago’s propositional verbs and iconic images enunciate a change of status and a sense of promptness necessary to face up to the status of the female, whilst in Catunda, the delirious micro-climates, protuberances and members — as dispersed as they are emphatic— obliterate any possibility of constraint.

In Hellenic Greek mythology, the Gorgon has always been represented by the monstrous and mortal mask that makes up her face. Sophocles called her ‘the girl with no door in her mouth’. In Catunda’s Deusa, we have a (double) Gorgo as one of the characters in the melting pot contained in its small circular territory. The presence of the Gorgo — a divinity in reverse, incapable of any ‘good deed’ — is a mark of insurgence.

In the middle of Chicago’s large painting Mother India, Shiva holds a baby in one of her arms, whilst her other members seem to be preventing the separation of four small human bodies. In Hindu cosmology, Shiva tends to appear either as a male or mixed gender entity; however, by subverting the traditional imagery, Shiva as imagined by Chicago is not only breastfeeding but is also pregnant: a woman Shiva.

Based on extensive research on the conditions of women in Indian society, Mother India also depicts, around Shiva, several scenes of suffering that evoke the violence of arranged marriages, of giving birth in unsafe conditions, of infanticide and the confinement of mothers. Surrounding Shiva turned into woman turned into mother, Chicago exposes an inventory of the systems that regulate the female experience.

An essentially ambiguous divinity, Shiva is responsible for both destruction and transmutation. It was also the power to metamorphize that turned the Gorgon into such a terrifying creature: look her in the eye and you’ll be turned into stone. Both mythological figures, therefore, deal with a sort of power that is as destabilizing as inventive.

The works of Judy Chicago and Leda Catunda converge in how they enquire about, convert, dismember, qualify and reconstitute the fabric of the world. As dissonant as they may be, both artists activate the diction and tonus of body parts that force them to stand out: fecund, hyperbolic or devouring elements, vibrating like vocal folds in our direction.

[1] Portuguese, unlike the English language, have gendered nouns and adjectives.

[2] Anne Carson, If Not Winter